21 September 2020

Edited and abridged by Marci Shore

KRZYSZTOF CZYZEWSKI: I’m here in Krasnogruda. It means at the border between Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus, in the northeastern corner of Poland. In my Borderland Centre, which, with my friends, I established 30 years ago, thinking of being more engaged in art, for solidarity with people, with community life.

Of course, during communist times we were in the underground. But the question for us was how to reach out. As an artist, culture, for me, means more than the event, more than artistic production. It’s creating a space for gathering together with other people, people raising courageous questions.

Our work is very much about the past, about memories. But we feel this is also work on regaining the future, which was taken from the people. The people here in the borderlands didn’t have a future. So they tended to do cruel, irrational things because they did not have a future.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: One of the striking things about our present circumstance is that the borderland between Belarus and Lithuania seems very, very far away from the borderland between Texas and Mexico. One of the tragedies in what’s happening on the border between Texas and Mexico is the people are not aware of this experience that you have. And I take it as one of our projects to bring that experience into a discussion about what’s happening in the United States as it borders Mexico, and actually as it borders the rest of the world.

DAN SHORE: I’m Dan. I’m still wondering a little bit why I’m here. But then I always wonder why anybody wants me anywhere. So I’m very comfortable being confused in these situations. I’m pretty sure I am the least thoughtful, the least philosophical, and you know least intellectual of all the people that I’m seeing on the screen here. But that’s okay.

I’m an opera composer. I write my own librettos, which probably is important in some way. It means that I have a lot of control over the stories I tell. And it takes a long time to write an opera. Once you choose a story to tell, you’re working on that story for many years. And as a result, I’ve tended to pick them very carefully and make sure that I’m telling something that I think will have a long resonance for anyone who watches it. So I’m always looking for a story that will have some kind of general appeal, even though it has to be very rooted in a specific time and a very specific place, with very specific people in very specific circumstances.

I have to confess, I didn’t really want to watch this film. It was a painful film to watch. I knew it would be a painful film to watch. I feel like I’ve been watching films like this my entire life. My nursery school teacher was in Auschwitz and then Bergen-Belsen. And I feel like I was exposed to that at an extremely young age. I feel like, at age three or four, we knew exactly what had happened during the Holocaust. We knew exactly what had happened to everybody. And in a way, I feel like that’s colored my entire life, and my entire approach to life.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: I’m going to interrupt. I’m going to say, “me too.” But that my experience was around the kitchen table of my grandmother. You know, I’m older than you. And it was around my grandmother’s kitchen table where people, survivors came for a good meal when they arrived in the United States. And I asked about those people who came to her apartment, who had numbers on their arms.

DAN SHORE: Everyone hopefully understands that Marci and I are brother and sister, and we grew up in a very similar way. When she talked about the neurotic catastrophists, I am absolutely one of them, with her, and I have been as long as I can remember. It probably does come from being exposed, like Jeffrey, to so many Holocaust survivors at such a young age. It was always a very, very real possibility to me that this is something that could happen to anybody, anywhere, at any time, with the least amount of warning.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: I think that one of the striking things about the film is knowing that where we are, it’s happening.

DAN SHORE: Right. It’s actually occurring. And occurring in precisely the way that we could have predicted it.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: Right.

DAN SHORE: There’s a playbook. And we have a copy of that playbook – you know, the 20th century. And every couple of days, I wake up, and I open up the newspaper, and there it is. Now they’ve gotten to page 34. And now they’ve gotten to page 42. And now they’ve gotten to page 77. And I feel like nothing is being done to stop this. It’s no surprise that these things are happening. The only surprise to me is that we live with so many people who did not see this coming, and so many people who are still in denial that it’s occurring.

VERA GRANT: I believe I bring in what I can only call Vera Mode. Because I feel like a nomad in so many ways, in terms of where my physical home is, where my intellectual home is, and where my heart is. I feel like I move between so many worlds. I consider myself a part of America. But I also recognize that being American is an abstract concept, of course one that gets stronger once you leave America and you confront people who are not Americans.

I grew up in an African-American neighborhood, a very impoverished one. And that was one of constant moving, the sense of home was constantly shifting. My parents, one, an extraordinary German woman whom I learned to think of as an ordinary German. She was not Jewish. She was a woman with North European heritage in Hamburg who survived the Third Reich. And my father is a Caribbean-American from the Virgin Islands. He emigrated to the United States, met my mother in Germany after the war, and then they married in Germany and came to the United States, in 1947, as an interracial couple.

They brought this marriage into a racist society that didn’t allow interracial marriages. So they became nomads within America. And when I grew up, they were trying to survive and make a life. Now, nonetheless, with that background, they both saw themselves as these Americans, they saw this American dream, what I call a techno-abstract idea of American immigration, the idea that even with that background, they could come here and create an American life.

Now my siblings and I, growing up with their having that dream, were living within the hood. We were in the ghetto. And our friends growing up were mostly African-Americans who migrated to New York from the south.

Right away, there was a disconnect. Because my parents both brought with them a sense of superiority. My mother’s Germanness and how she viewed the world, and my father’s upbringing in a Caribbean-Danish culture that viewed African-Americans as less, less than. . .

But I grew up within the New York City school system and with Jewish teachers. So I didn’t learn about the Holocaust at three or four, but I learned about it at seven or eight. I was watching Holocaust films. I was learning what had happened from my teachers’ perspectives, and dealing with that horror as a child, and being confronted as being German by these Jewish teachers. There was another German student in the classroom. We suddenly bonded as friends because we were both German. And the teacher kept talking about Germans. And we felt like: wait a minute, is this true?

My internal family dialogue around the Holocaust and Germany was one of avoidance. My mother didn’t want to talk about it. She didn’t want to talk about her role. She didn’t want to talk about what she went through. It was all about the bombing of Hamburg, the carpet bombing of Hamburg. That’s all the war was about.

What’s happening today – the caging, the torture, really, of children at the border – brings back for me so many comparisons. I want to compare it with the deep wormhole that I went into in Holocaust studies, which Marci knows about. And it became an obsession to learn more and more about it.

But it also brought up other comparative horrors. It brought up the separation of children in the American slavery system. Children were separated from their parents there. The separation of children of indigenous peoples in the United States and other lands, where they were taken from their families and put in these “civilizing” boarding schools. I even compare it to our kind of state incarceration system, where parents are removed from their children.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: Tyrone, are you there?

TYRONE: (painting the walls) Yes, I’m here. I’ve just been quietly listening, waiting my turn.

DAN SHORE: It’s funny, because I know Tyrone, even when I don’t see him, I can feel his enormous personality jumping out at me.

MARCI SHORE: I like the orange.

TYRONE: Thank you. My mother likes a lot of color, as do I. I’m not really a muted person. So I am a friend of Dan’s. He and I have collaborated on many projects. Chief among them is Freedom Ride. I’m from New Orleans. And when he was professor at Xavier, and began to write the opera, I was a part of some of the early performances. And I continued to sing excerpts from Freedom Ride when I lived in New York, at Opera America, at various fundraising events and such. And then Chicago Opera Theater hired me to sing in the world premiere. And I thought Dan could speak well for both of us because I don’t know why I’m here. I’m certainly not a part of the intelligentsia and academia and such. But I think I do have interesting things to say. And as a Black queer person and a musician, I run into this kind of conversation all the time, about what can be said, and what we shouldn’t say.

If you try to make a comparison to the Holocaust, it just feels – it feels cheap. It feels low. And so I get that. And I can understand how AOC’s comparison of the children in cages at the border to “concentration camps” strikes a nerve. I totally understand. Because as a Black American, as a queer person as well, there are things that you just don’t want to hear non – non –. . . people say. Or you don’t want to hear comparisons being made.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: I want to say, Tyrone, that it’s kind of interesting that, I found the Holocaust Museum’s response profoundly appalling. It’s exactly the kind of comparison just makes complete sense to me. AOC did not offend me. One of the problems I think that we have in this world of multiple images, and performances, and spectacle, it’s hard to actually comprehend what we’re seeing, or we see but we don’t perceive. And that simple comparison actually made it clearer to me what actually what was happening on the border.

TYRONE: Absolutely. I am not saying that I agree with the sentiment.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: No, I know that.

TYRONE: But just that I understand. And you know, we have this sort of thing where – I assume you’re Jewish. Because you said that you weren’t offended by the statement.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: That’s exactly right. I’m Jewish. My name announces it very clearly.

TYRONE: Goldfarb. Like the color gold. It’s beautiful.

You know, you take a person like AOC, and I always, in my relationships, want to give the benefit of the doubt and also consider the track record. Is it coming from a person that has a record of being on the right side of things? If the answer is yes, then maybe I could give the comment a second thought, look at it from a different angle, instead of immediately being like, (in an aristocratic tone) “oh, how dare you?”

VERA GRANT: I think that each of these kind of state structures that descended into hell has its own peculiarities. To say that now what’s happening right now at the border, is like the concentration camps, in some ways, yes. But I can also feel the sentiment: is that legitimizing this suffering? As if the suffering would not be acknowledged as real without comparing it to something that’s more well-known, and more financially and intellectually supported as a major sphere of discourse?

Nonetheless, I feel there is value in comparative analysis. If you take a less conflicted moment, where George Frederickson, the historian, was comparing South African apartheid to American race structures, he received so much flack. But he was trying to give people another way of seeing something they’d become familiar with by making it unfamiliar.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: Inevitably we act in the present, reflecting on the past, and imagining a future. I’m a student of Hannah Arendt.

KRZYSZTOF CZYZEWSKI: An avalanche of killings never started as a huge thing. Auschwitz was something connected to daily life and small events. That’s how it starts. You never know how it will end up. But you should pay attention to the small things.

Your traumatic memories somehow keep you imprisoned in your own memories and the past of your own nation, group, culture. And it prevents you from thinking about or being more empathic with other tragedies. It can happen like that. You know, it’s not obligatory. But I have this experience, that it is like overshadowing – what you experienced in the past, or what your family experienced in the past overshadows the whole reality. And there is little room to feel that others can suffer as much. So what do we do in Borderland, in art, is to invite people to be more hospitable, to give them room. And I think it’s the role art can play, So you can be nervous. “But go on. Don’t give up. Don’t say that they are not right, that they don’t understand, they can’t understand it, and so on.” Try to find tools – expressions, forms, language. Opening new rooms, new spaces, giving voice to other people, other suffering. So from one side, you can say, the Holocaust was such a big trauma that it is incomparable with anything. But does it mean there is no room to understand Ukrainian sufferings under these totalitarian times?

DAN SHORE: I feel like that’s the work of narrative art. It’s not just that you’re telling a story, it’s that you’re creating characters. And by creating a believable character on stage, you’re inviting the audience to get into the mind of this character. Can you take a moment and think about what they are experiencing, what they are feeling? The difficulty in theatrical works is that you want to put different characters on stage who do not all share the same opinion, in fact, the more the opinions of the people on stage are in violent conflict with each other, the more interesting. But you also have to create them all in a way that’s completely sympathetic. And hopefully, in some sort of bizarre, Pollyannish fantasy world, this is helping an audience practice the art of saying: Okay, I don’t agree with this person I’ve just met, but I can sort of understand where they’re coming from now. Because every time I’ve read a book, or every time I’ve seen a play, or an opera, or a musical, or watched a movie or a TV show, I have practiced what it is to get inside the mind of somebody who does not necessarily think exactly the way I think.

VERA GRANT: Tyrone, it’s lovely to see the flashes of you painting. Right now, I’m working as a curator and a writer. And I have the opportunity to work with so many different kinds of artworks. And what I try to do is to put them in dialogue around a particular theme. One project I recently did was inspired by a Candida Hofer photograph of an empty cathedral. She makes these enormous photographs of empty institutions, in this case, the Catholic Church. Then there were dialogues set up around it. One was about the sexual abuse that occurred in the Catholic Church. And the dialoguing artworks were set up in a thematic view called “Come See About Me.” And when you have a dialogue around something like that, you have a figure – the perpetrator – who becomes almost irredeemable. How can this figure invoke any empathy? How can this figure be someone you want to have a dialogue with? At what point does the conversation break down? Yet so many of the perpetrators around sexual abuse were themselves abused. And it’s a vicious cycle. Right? So if we cannot bring empathy to that figure, then who are we cutting out of the conversation?

MARCI SHORE: Dan wrote this opera, which Tyrone starred in, based on the Freedom Rides. It’s set in New Orleans in 1961. And the drama is about a young woman who has to decide whether or not she’s going to get on the bus. It’s a kind of existentialist opera. She’s a young Black woman. She’s afraid. She gathers strength, she vacillates. And we see her come to that choice. But Dan does not put the white supremacists on stage. Nobody from the Ku Klux Klan appears in that opera. There are different characters: some are more likable, some are less likeable, some you identify with more intensely, some seem braver than others. But the really bad guys are not on stage. At one point, there’s a bombing. And you know that the racists are implicitly there, they’ve set off the bomb, but they don’t appear as characters. They don’t get their own aria. They don’t get to sing. Dan, in one interview you said that you didn’t know how to put a completely unsympathetic character on the stage.

DAN SHORE: That was a distance too far for me. I thought: I can understand somebody who is too scared to do something or is too nervous to do something, or doesn’t want to get involved with something because they think it’s dangerous. But the thought that somebody would actually show up at a bus station with a baseball bat and start pulling people off of a burning bus and swinging a bat at them, I just thought: I don’t understand that person. And I don’t want to understand that person. That’s a personal leap that I never want to make. And I didn’t want to put someone on stage if I couldn’t put them up there as a well-rounded human being.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: So if I understood Vera correctly, she’s challenging that: that there is an imperative that we actually consider the member of the Ku Klux Klan as well. What brought him or her to that bus stop? Is there anything that we could – that we can – do to actually stop that?

VERA GRANT: I appreciate what you just expressed. Because it’s hard to say: what about the perpetrator? But there has been work that makes us take the evil out of that word in order to say “you know, we’re all born on this earth. So how did you come to be. . .?” But, if you’re closed off – and I appreciate what Krzysztof was saying – if you’re closed off in your own sphere of memories, and there is no way to broach that dialogue, then what is that saying about us?

A friend of mine tells me, in some arguments about prison, she’s like, “Oh, Vera, some people belong in prison, okay?” I’m always like: look, that’s not my point. I love Christopher Browning’s work on ordinary policemen in Nazi Germany, how they got caught up in and became part of that structure of the genocide.

I think about ordinary Americans, the people in those lynching photographs from the latter part of the 19th century through the mid-20th-century. I’ve said: “Could you ask your parents? Ask your parents who in your family went to these picnics and celebrations? What were they thinking? What are they thinking now when they see the caged children?” You hear empathy, but at the same time a refusal to want to change the social order. You can empathize and still be part of a perpetrating group.

KRZYSZTOF CZYZEWSKI: Following what Vera said, and coming to the question Marci asked Dan, as an artist, about these negative characters – what interests me in art is transgression, transformation, a change of character. That something starts with someone being, for example, a perpetrator. But something is happening. And art allows us to express a possibility of change. And for me, as a bridge builder, the crucial thing is to develop a culture that can help people change, a culture that does not pin them to the wall and stigmatize them – “oh, you are antisemitic,” “you are homophobic.” When you start with this language, you stigmatize people. Józef Tischner, the Polish philosopher, would say that we closed people in hideouts. And there is no way for them to go out from there. So I’m thinking about art in terms of how we can help people to go out of hideouts? To have the possibility to change and not be stigmatized forever?

TYRONE: I feel conflicted. Because I think I hold both views in one body. I do agree that we live in a cancel culture, we are super quick to just cancel people. You’re done. You said this, bye. We don’t want to hear from you anymore.

But I also agree with Dan in his decision not to sort of amplify those voices in his work of art. As Oprah said, years ago, no longer would she use her stage as a place for people to come and share their hate. What we are missing is the voices of the marginalized, the voices of the disenfranchised. Those are the opinions we need to hear. I don’t need to hear any bigoted person tell me why he or she feels the way they do about race. I don’t need to hear that. That is of no interest to me because I’ve already heard it. It’s well documented. We already know what they’re going to say. But at the same time, I do feel like we do need to keep space for people to change, for people to grow. But those aren’t really the KKK voices. I have very little hope, very little trust, very little faith that those views and opinions will change with anything that I can say.

I could change. But that’s because I’m always open to listening to other thoughts and views.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: I’m thinking, in the back of my mind, what to do with Donald Trump and the people who support him?

TYRONE: Beat him.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: Beat them, yes, that’s right. So how do we beat them? Many years ago I was subjected to the draft during the Vietnam War. And I decided, though I’d like to call myself a pacifist, I couldn’t, because I knew that I would very willingly kill Nazis to defeat them.

But I don’t think the answer to Donald Trump is violence. I live in very blue America. But today I passed a house that was just covered with Trump propaganda, and a warning to liberals not to enter this house. It was really quite atrocious.

DAN SHORE: Maybe you were in my neighborhood in Virginia?

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: It’s really in a little corner of where I live, almost hidden close to a forest, where he very proudly – and I’m assuming it’s a “he” – is presenting all this stuff. We have to defeat them. What about the people who see these images of what’s going on on the borders of the United States, and they actually don’t recognize their own complicity? To go back to the film that we’re talking about, they don’t see the clear analogy, or even a kind of common experience between what happened then and what’s happening now? How do we confront this? How do we move them? I’m relatively optimistic that Trump is going to be defeated. But I’m in total despair that 40%-plus of my fellow citizens are going to vote for him, which means voting for the cages.

TYRONE: It’s mind-boggling.

DAN SHORE: I think the thing is – and this goes back to something that Tyrone said earlier about people who aren’t going to change – as a dramatist, I’m only interested in change. I’m only interested in characters who will change. So if there is somebody who is completely set in his ways, I don’t need to put them on stage.

I think it’s the same way with dialogue. If you run into a group of ten Trump supporters, and nine of them are going to vote for him no matter what, they are set, they are already 100% in that camp, I feel like the dialogue with them is less important than with the one person who could maybe go one way or the other.

And I think that’s the thing that we miss on social media. Because we end up in arguments with people we will never persuade. What we need to look for are the people who maybe think one thing, but genuinely haven’t thought about something else, people who, if they really understood what was happening at the border, maybe would think about things differently.

MARCI SHORE: Kalev, my 10-year-old who just came by, never wants to go to sleep if I’m still awake. We were talking recently about the elections, our kids are obsessed with the elections, because they’re our kids. And I told him: we don’t need all 40% of those people who vote for Trump to change their minds, we need maybe 3%, 4%, 5%, we need that small margin to change their minds. And Kalev said: yes, but it would be better if all 40% changed their minds –

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: I agree with him.

MARCI SHORE: Yes of course it would be better. There’s the practical-normative question, how do you change people’s minds? But then there’s also the question of understanding. What are the epistemological limits of our ability to understand? On what basis are we able to understand other people? Is empathy always on the basis of some kind of comparison?

To do any kind of art – any time you put a character on stage or in a novel – is an act of faith that some kind of understanding is possible. Not that perfect understanding is possible, but that some kind of understanding is possible.

So then the question is: If we’ve reached the apparent limits of that understanding, is there a way to push it further? Okay, we’re never going to get to perfect understanding. But can we get further?

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: I’m understanding my role as being that of the moderator. But at this very moment, I’m not feeling very moderate. Something that Vera said in introducing herself, I identify with very strongly. I’m an American, but I have a complicated family history. My adopted country, Poland, is an important part of my identity. And I’m Jewish. And being a Jew in America seems to be easier than it was when I was a kid, but not as easy as when my children were kids. And therefore I feel some otherness in this Christian country. And yet, when I go abroad – and this is what Vera said – when I go abroad, I realize how American I am.

That Americans are supporting Trump makes me wonder whether I’m American at all. There’s something profoundly unsettling about the ascendance of Trump, but even more the support that he’s getting from the American public, which makes me feel alien. And I wonder, is there a way to bring forward the American identity that I have, which is a kind of anti-racist identity, the old democratic promise, the pluralistic identity. I never felt more American – or more positive about being American – than when Obama won the caucuses in Iowa. And I’ve never felt as alienated from my country as right at this moment.

DAN SHORE: It’s interesting what you said about Obama. My wife and I rarely watch TV. But during the Obama inauguration, of course we were glued to the TV set. We didn’t want to miss a moment of it.

And as musicians, what we talked the most about was the music. The Army band came out. And the Army musicians were playing. We said, oh, it must be so cold outside. And they’re playing.

And a few months later, my wife enlisted in the Army. And she went through basic training. And for eleven years now, she has been a full-time musician with the United States Army Band. And had that been the Trump inauguration that we were watching, it would have never happened. But she joined the Army at a time when there was still so much hope and enthusiasm. And this idea that maybe, maybe things could be moving in a more positive direction. And it’s incredible how quickly that has tanked eight years later.

One of the things that most of the people in the band are allowed to do is march during the inauguration. And of course everybody was gunning up for a chance to march at the inauguration when they thought it was going to be Hillary Clinton. And once it became clear, that that was not going to happen, the mood in the band changed. All of a sudden, nobody wanted to march. And instead of higher-ranked people letting the lower-ranked people march – in the spirit of ‘you’ve earned this, you deserve this spot’ – it became: okay, all right, I’m higher ranked than you, I will suffer through it. I will go out and you can be spared. We won’t make you go through the humiliation of participating in this service.

VERA GRANT: I want to just add that we’ve been saying “Trump supporters.” But I think we’re also talking about a wide swath of people who are not overt Trump supporters but are complicit in how they’re letting this “Trump supporter” be the visual. They want to see that judge, right? That’s the latest discussion. They want that conservative judge seated. They want the Trump policies.

DAN SHORE: Hey, Kalev.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: Wow. It’s very late.

MARCI SHORE: Yes, it is.

KALEV: No one cares if it’s late.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: No one cares?

DAN SHORE: He doesn’t want to miss any of the excitement.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: I’ve dedicated my life to social science. But I turn to the arts to do what we can’t do. And it seems that one thing we can’t do is we can’t commit to ambiguity. Ambivalence is not the stuff of policy science. But it is the stuff of music and theater and drama and painting. I’m stuck between both appreciating all of that and feeling that somehow we have to do something now, that we have to have this discussion, as Marci wanted to, before the election. Why before the election? Can we do anything?

MARCI SHORE: Like everybody, I’ve been tearing my hair out: what can we do? Haven’t we done everything already? Haven’t we written everything already? Why are we constantly talking to one another?

Kalev was looking through The New Yorker a couple of months ago, and he wanted me to explain various political cartoons to him. And then he said: “but when the Trump supporters read this, won’t they understand how horrible Trump is and change their minds?”

And I said: “the thing is, no one who supports Trump reads The New Yorker.” Kalev asked, “how do you know?” And I said: “I just know. . .”

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: It’s an exaggeration, but –

MARCI SHORE: But we are talking to one another. We don’t really have contacts on the other side. Of course there’s a range. There’s always a range. There are the center-right conservatives. There are the Lincoln Project people. There are the conservatives like Anne Applebaum. But that range never includes everyone. We don’t invite members of the Ku Klux Klan to come discuss racism at our seminars. There’s always a line. On the one hand, there’s the cancel culture, which we seem to agree is not the right solution, is exclusionary, and cuts off as opposed to opens dialogue. And on the other hand, there’s the radical inclusiveness that says why don’t we invite the Klu Klux Klan to come talk to us, which we can’t stomach. How far can we go? And is there some way – is there something we haven’t thought of yet that will somehow open us in a way that enables us to make some connection we haven’t made before, or enables us to reach other people in a way we haven’t before? Are there people who still might be transformed, who are still possibly open? Might unexpected things happen?

I’ve also been watching Belarus, and looking at the masked guys in the riot police brutalizing the protestors, and thinking: how many of them do you need to defect before the whole situation turns around?

I remember that moment from watching the Maidan in Ukraine, in 2014, during the massacre. I was following the live feed in Polish, on Gazeta Wyborcza, it was the best one. There’s a sniper massacre going on in Kyev. And Yanukovych is calling up different divisions of the riot police and the militia. And then the news comes in that a certain division in Lviv “crossed over to the side of the people” – that is, they refused to go. Some time passes, and the news comes that another division has changed sides. And so on. And at a certain moment you realize that a tipping point has been reached, and it’s all over. And now watching Belarus, and seeing some of those guys defect and throw away their uniforms, I’m asking myself: how many do you need to change sides before you reach the tipping point? And I’ve been watching America and asking myself the same question: how many, what percent, what margin, when do we reach a tipping point?

VERA GRANT: I love that idea of the tipping point.

And just going back to the cartoons in The New Yorker. I remember a cartoon I used to love so much, from the 1990s. It was a young woman bringing her boyfriend home. The parents are on the couch. He comes in the door. She introduces him. And the parents say: “Oh, he’s a terrorist. Thank God. We thought you said he was a theorist.”

Now, that cartoon would not have played after 9/11.

JEFFREY GOLDFARB: Right.

VERA GRANT: You wouldn’t have seen a cartoon like that. Then you have the Arab Spring. It was such a joyous moment. And you look back in despair at what’s happened in some of these Arab states. Where is the hope? These moments where you see a tipping point coming, and then you lose it, for me it’s like a tightening of a vise.

So I love the tipping point. But what are our metrics for seeing if we’re headed there or if there is no there there?

JEFF GOLDFARB: If Biden wins, what then? That guy whose house I passed during my morning run, he’s going to still be there. The Supreme Court, we’re stuck with it. The racism of the police is not going to melt away. The tragedy of the lands that Krzysztof finds himself in is that after the liberation the oppression reproduced itself. And I think that discussions such as the ones that we’re having today illuminate, give us resources to actually make it so that the abusive priest, the abusive human being isn’t followed by another abusive human being.

KRZYSZTOF CZYZEWSKI: I think that we are more or less the same people, and the borders between us are not definitive ones, that they are much more flexible. And that’s why my optimism is still alive. You know, a few years ago, people were thinking about Belarussian society that it’s too Sovietized, that democracy is not for them, that they are an eastern country which will never accept democratic rules, and so on. And suddenly you have an amazing society, an uprising, a movement. You know, they are the same people.

To give you another example, recently, I spoke with Martin Šimečka. And he wrote a book about Slovak society, a small country, whose people are traditionally conservative, with a strong fascist movement in the society. But recently, Mrs. Čaputová appeared. And the same people voted for her. She found a way to appeal to the same people, to their positive side.

Poland is the country with Kaczynski. Poland is a country which helps people to express their negative emotions. We have leaders, we have media, who appeal to the dark side of the people, and to their negative emotions.

VERA GRANT: I have people within my immediate family who are Trump supporters. Fully educated, African-American – when they want to be.

Marci, I was reading that in Belarus, where there have been women’s protests on Sundays, the protestors were threatened with having their children taken away from them. So this has become a new kind of arrow of ammunition.

DAN SHORE: I really enjoyed what you said before about committing to ambiguity. And I think that is a fundamental part of what we do as artists, yes, is we commit to ambiguity. And I’m going to say that my sister’s historical research to me, has always been founded in ambiguity. It’s always like: well, this happened, but also this, and here are five opposing voices that I’m going to put together.

On the other hand, at some point, there is an election. And at some point, somebody is going to fill in the little circle for Democrat or they’re going to fill in the circle for Republican. So I think we have to remember that there is ambiguity, but there is also sometimes a yes-or-no decision.

My opera Freedom Ride is about a woman deciding whether or not she’s going to get on this bus and participate in the Freedom Ride. And in the end, she either does or she doesn’t. The entire opera can be ambiguous, but in the end, she’s going to do one thing or the other. Marci talked about finding a tipping point, but I think we also need to look for tipping points inside of ourselves. Because at some point that ambiguity has to push you to one answer or another answer. All the ambiguity in the world doesn’t absolve us of the responsibility to sometimes say yes or no.

Tyrone Chambers has been in Germany since the summer 2017 and frequently performs around the country. The Süddeutsche Zeitung heralded him for singing with “tenorissimo…, fine in the heights, elegantly gliding on the tempi waves and in forte with powerful dedication.” For the last two winters he’s toured The Andrew Lloyd Webber Musical Gala throughout western Europe and Scandinavia. The 2019-2020 season was full for Mr. Chambers with performances in Brazil, in Germany at Papageno Musiktheater in Frankfurt and with Opera et Cetera, and in the USA. He will return home next season for the role of Monostatos in The Magic Flute. In February this year just before the world changed, he premiered the role of Russell Davenport in Dan Shore’s Freedom Ride at Chicago Opera Theater. Mr. Chambers resides in Mainz, Germany.

Krzystof Czyżewski is a practitioner of ideas, writer, philosopher, culture animator, theatre director, editor. He is co-founder and president of the Borderland Foundation (1990) and director of the Centre “Borderland of Arts, Cultures and Nations” in Sejny. Together with his team, in Krasnogruda on the Polish-Lithuanian border he revitalized a manor house once belonged to Czesław Miłosz family, and initiated there an International Center for Dialog (2011).

Among his books are: The Path of the Borderland (2001), Line of Return (2008), Trust & Identity: A Handbook of Dialog (2011), Miłosz – Dialog – Borderland (2013), Miłosz. A Connective Tissue (2014), The Krasnogruda Bridge. A Bridge-Builder’s Toolkit (2016), A Small Center of the World. Notes of the Practitioner of Ides (2017, Tischner Award for the best essayist book of the year), Żegaryszki (2018, haiku poems), and Towar Xenopolis (2019).

Initiator of intercultural dialogue programs in Europe, Caucasus, Israel, Central Asia, Indonesia, Bhutan and USA. Teacher and lecturer, a visiting professor of Rutgers University and University of Bologna.

He received the title of the Ambassador of European Year of Intercultural Dialog (Brussels). He is a laureate of Dan David Prize 2014 and Irena Sendlerowa Prize 2015. Together with the Borderland team he is the 2018 Princess Margriet European Award for Culture (Amsterdam) laureate.

Jeffrey C. Goldfarb is the Michael E. Gellert Professor of Sociology at the New School for Social Research. He is also the Founder and Publisher of Public Seminar. His work primarily focuses on the sociology of media, culture and politics.

He also runs the Democracy Seminar, a worldwide committee of scholars, journalists, activists, and citizens who seek to understand the origins of the threats, to analyze their dimensions and, most importantly, to exchange ideas and experiences about how to oppose them.

Vera Ingrid Grant is an independent curator and writer based in Ann Arbor MI. She most recently served as Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs at the University of Michigan Museum of Art (2018-19). Grant is founding director of the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art at the Hutchins Center, Harvard University and an associate of the Hutchins Center, Harvard University. Grant has an MA in Modern European History from Stanford University, was a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Hamburg, and was Associate Director for the Program in African and African American Studies (2001-2007) at Stanford University. Her recently curated exhibitions include: Cullen Washington, Jr.: The Public Square (2020); COLLECTION ENSEMBLE (a reinstallation of the permanent collection) and Abstraction, Color, and Politics (2019) for the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA); Carrie Mae Weems: I Once was a Girl (2017); Harlem: Found Ways (2017); THE WOVEN ARC (2016); Art of Jazz: NOTES (2016) at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery (Harvard University); and Persuasions of Montford at the Boston Center for the Arts (2015). Recent publications include: Harlem: Found Ways (2017), editor; author of “Mobilizing Aesthetics (Ethelbert Cooper Gallery, 2017);” Luminós/C/ity.Ordinary Joy, editor; author of: “E2: Extraction/Exhibition Dynamics” (Harvard University Press, 2015); “Visual Culture and the Occupation of the Rhineland,” The Image of the Black in Western Art, Vol. 5, The Twentieth Century, (Harvard University Press, 2014); and “White Shame/Black Agency: Race as a Weapon in Post-World War I Diplomacy” in African Americans in American Foreign Policy, (University of Illinois Press, 2014). Grant has held a number of fellowships: the Center for Curatorial Leadership (2015-16); the Studio Museum in Harlem (2014 and 2015); the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute, Harvard University (2012); and Visiting Scholar at the Center on Intersectionality and Social Policy, Columbia Law School, NY (2011). Grant’s recent public lectures include: The West Michigan Area Show “Juror Insights” (Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Spring 2019); “The Collector’s Eye:” a talk with Collector George N’Namdi (N’Namdi Gallery, Detroit, MI Summer 2019); and “Curating Unsettling Legacies” (The Scarab Club Clyde Burroughs Lecture, Detroit, MI February 2020).

Dan Shore’s most recent opera, Freedom Ride, premiered this year to critical acclaim at Chicago Opera Theater. The composer and playwright’s many works for the stage include The Beautiful Bridegroom, An Embarrassing Position, Works of Mercy, Travel, and Anne Hutchinson. An alumnus of the BMI-Lehman Engel Musical Theatre Workshop, a Fulbright scholar, and a two-time winner of the National Opera Association’s Chamber Opera Competition, Dan holds a B.M. and M.M. from the New England Conservatory and a Ph.D. from the City University of New York. Former faculty at Xavier University of Louisiana, Baruch College, and Emerson College, Dan is an Assistant Professor at the Boston Conservatory at Berklee.

Marci Shore is associate professor of history at Yale University. She is the translator of Michał Głowiński’s The Black Seasons and the author of Caviar and Ashes: A Warsaw Generation’s Life and Death in Marxism, 1918-1968, The Taste of Ashes: The Afterlife of Totalitarianism in Eastern Europe, and The Ukrainian Night: An Intimate History of Revolution. In 2018 she received a Guggenheim Fellowship for her current book project, “Phenomenological Encounters: Scenes from Central Europe.”

This contribution is part of the larger forum engaging artists and authors, from very different places and writing in very different genres, in a conversation on “the uses and disadvantages of historical comparisons for life.” The idea initially arose in response to the American presidential administration’s family separation policy on the southern border. A short documentary film, The Last Time I Saw Them serves as a point of departure. The intention is to provoke a discussion that could be an Aufhebung of the ‘is Trumpism fascism?’” debate: what can and what can we not understand by thinking in comparisons with the past?

Read Marci Shore’s introduction to the project here. Find the Table of Contents listing all contributions here.

The project is a collaboration between the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University, the Democracy Seminar, and the Transregional Center for Democratic Studies (TCDS) at the New School for Social Research.

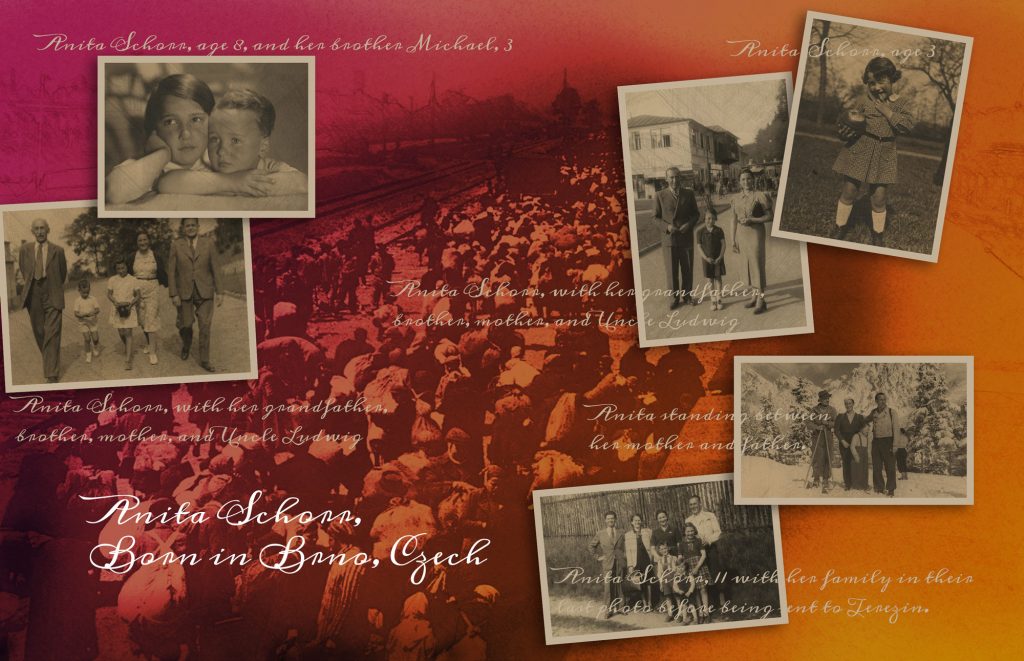

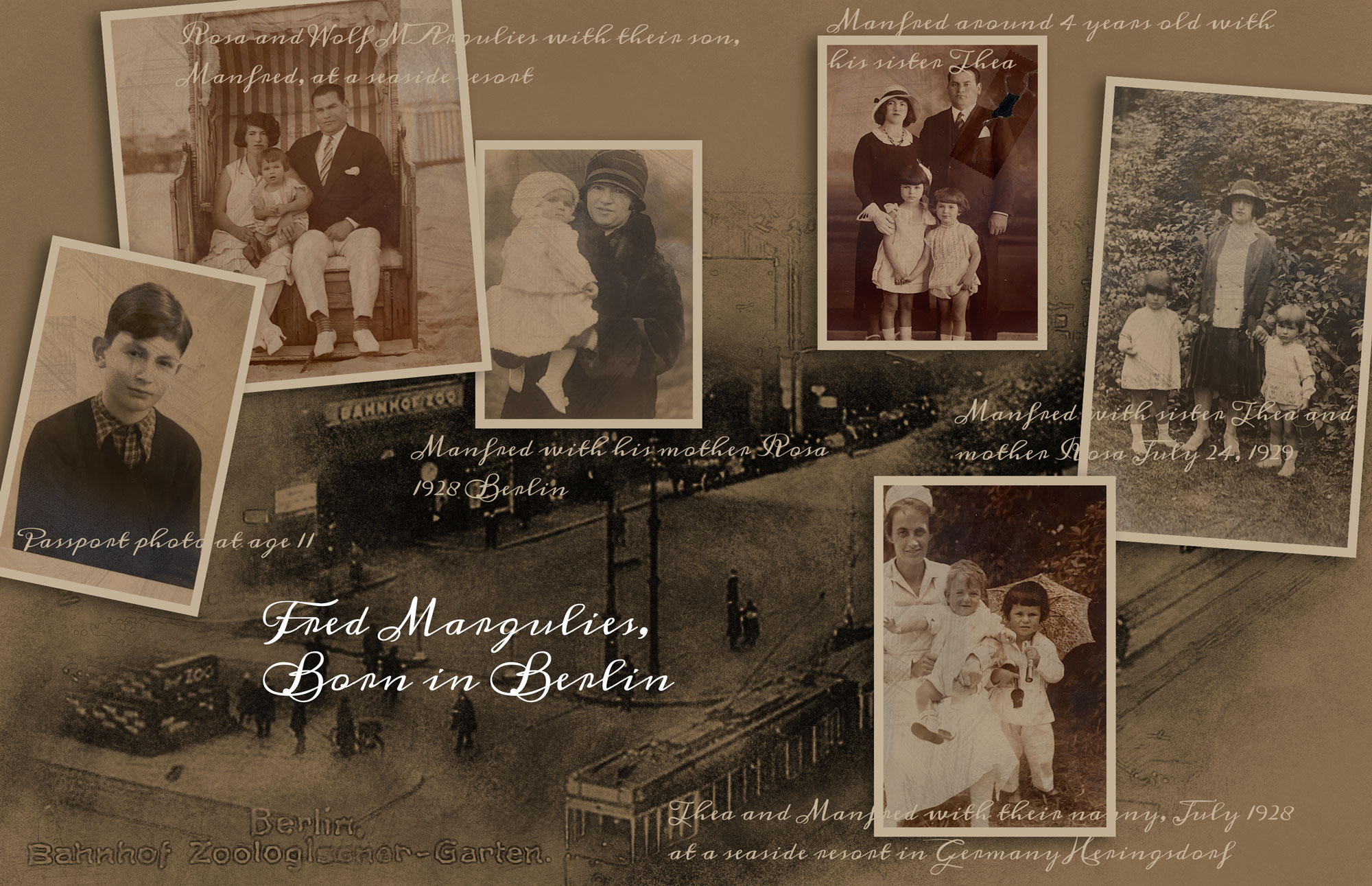

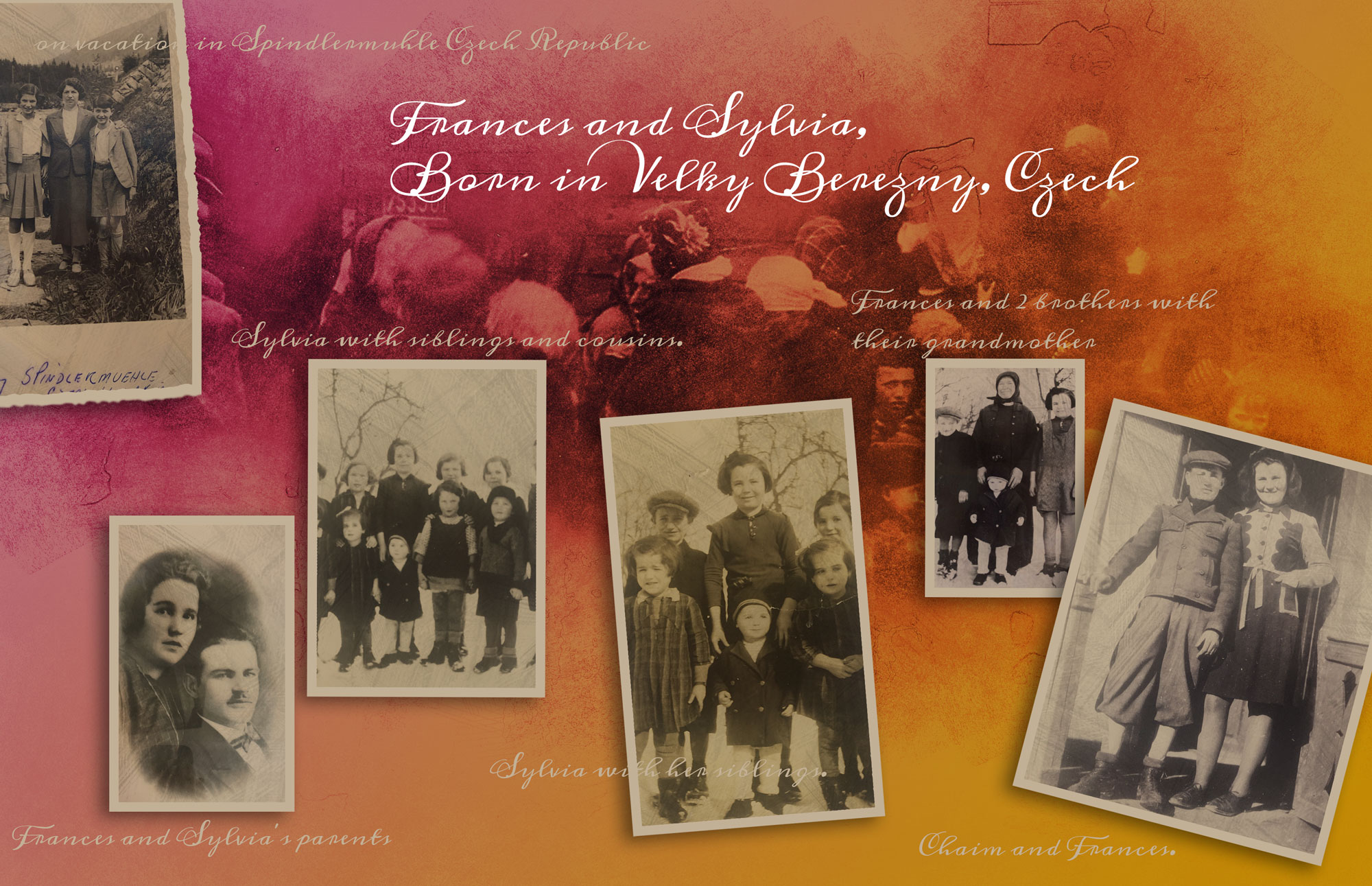

Image created by artist Kenan Aktulun; the images come from each of the families. (Fortunoff Video Archive).

‘The Uses and Disadvantages of Historical Comparisons for Life’